Getting Medieval with Big Data: David J. Herlihy (1930–1991), the first digital historian

David J. Herlihy’s personal research subject catalog, featuring medieval subject categories of “Witches,” “Uncles,” “Possession,” “Disease,” “Education,” “Names,” and “Purgatory.” Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Almost 60 years before the terms “big data” and “digital humanities” were in use, and before economist Thomas Piketty compiled and analyzed his enormous data set, one man pioneered the use of computers for data-driven historical analysis. David Herlihy, a historian and early demographer of Medieval European populations, went to great lengths to access and master the use of the earliest commercial computer, and subsequently revealed a surprising and more accurate picture of Medieval life than known to his predecessors.

Herlihy was a pioneer in the use of computers to analyze socioeconomic trends of the middle ages. In 1953 IBM corporation delivered the UNIVAC I computer to the U.S. Census Bureau. The UNIVAC was the first commercial computer to attract widespread public attention. Linguistic and literary scholar and Jesuit priest, Father Roberto Busa, is widely credited as the first digital humanities scholar, having collaborated with IBM to produce the first machine-generated literary concordance in 1951. Herlihy is acknowledged as the first historian to apply the power of the UNIVAC computer to historical census, property, and tax records, providing unprecedented social and economic insights to our understanding of the past. He utilized computers for his entire career to compile and analyze large quantities of data (“big data” in today’s terminology).

As a young Fulbright fellow, Herlihy based his 1954–1956 PhD research and first book, Pisa in the Early Renaissance: A Study of Urban Growth (New Haven: Yale University Press 1958), on Pisan notarial chartularies in the State Archives of Pisa. In a 1990 address about his work for the Galileo Galilei prize, he described the evolution of his research process, and his enthusiastic embrace of computers:

David J. Herlihy’s hand-drawn map of various quarters of an Italian city. Herlihy would relate statistical data to specific areas of cities, towns and surrounding areas. Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

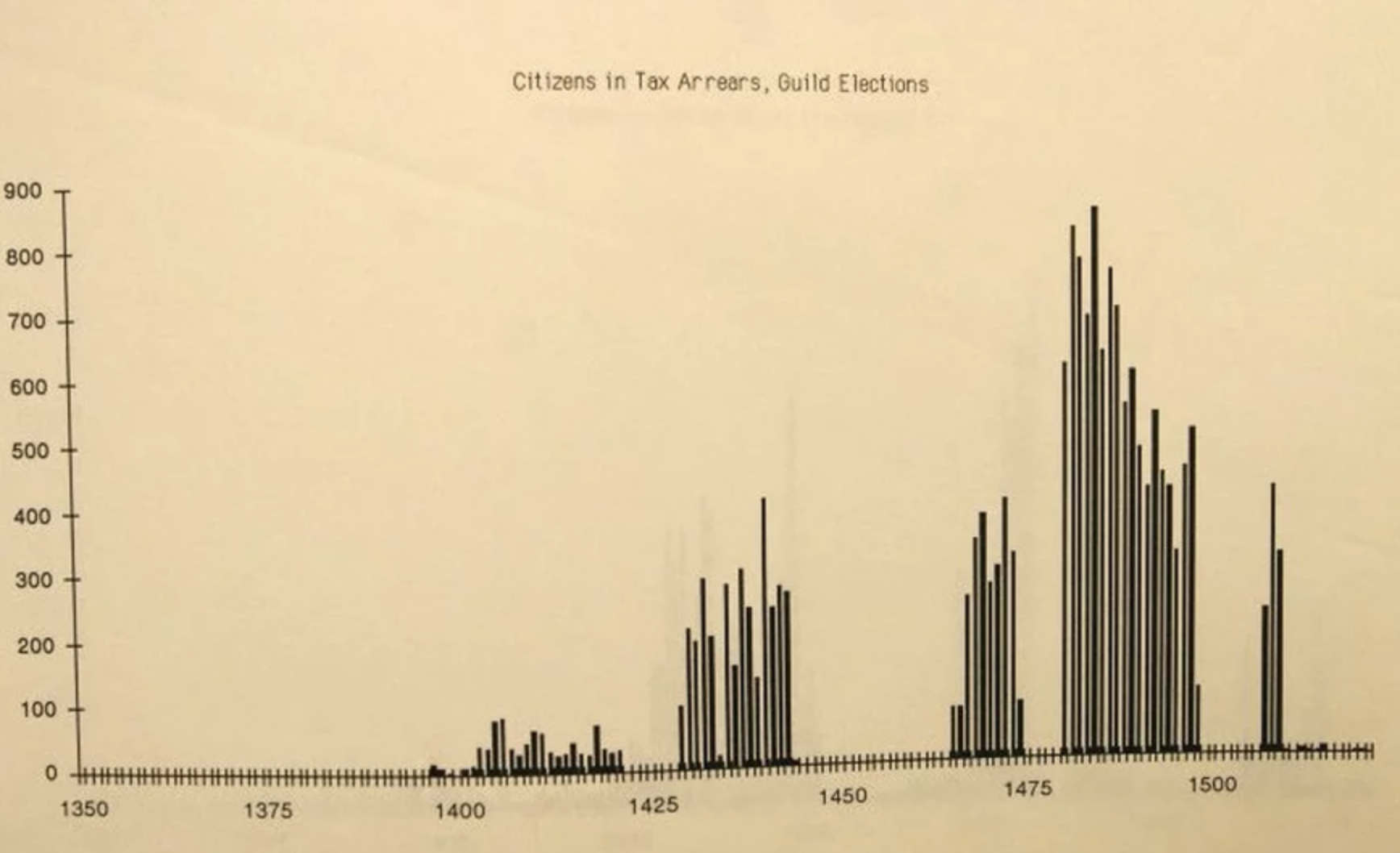

“Citizens in Tax Arrears, Guild Elections, 1350–1525.” Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

“It ought to be possible to show certain changes over time in the large runs of private acts out of the central Middle Ages. Were payments made of coined money or in money substitutes? [and he poses a half dozen or so more questions he would like to ask of the source]. By tabulating the answers to these and similar questions one could illuminate, I believe, long-term trends over time. One could objectively estimate trends. These illuminated trends would lay the basis for surer inferences concerning changes in the economy. I began this work by tabulation by pencil in documentary series the number of payments in money as opposed those not in money and so forth.

By the 1960s, two changes lent me encouragement in this work. The first was the growing application of quantitative methods to historical materials. While the methods I was using could only suggest trends and not estimate outputs, nonetheless the new methods were showing that a greater variety of documentation was susceptible to statistical analysis than was formerly believed. The second novelty of the 1960s was the advent of the computer. It promised relief in the supremely boring tasks of tabulation. It was still necessary to convert the documentation into machine-readable form, but once that was accomplished, the computer allowed the data to be viewed in almost unlimited ways. The joining of the computer and the propensity of the medieval Italians to generate documents was a marriage made in heaven.

A culmination in this use of statistics in the analysis of medieval records was a project undertaken in 1966, to study with the aid of computer the great Florentine Catasto of 1427–1428. The document was well known to historians, but is very size was an obstacle to its efficient study. It surveyed 60,000 households and 260,000 persons across nearly the entirety of the Tuscan lands ruled by Florence. I first encountered it myself while working on a study of Pistoia in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. I remember how amazed I was to find recorded in its pages not only the names of the Pistoiesi but also their ages, relationships within their households and belongings. When I finished my study of Pistoia [Medieval and Renaissance Pistoia: The Social History of an Italian Town, 1200–1430, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1967] I decided to undertake an analysis of the entire survey.”

“Women’s Occupations (by wealth)”: Computer-generated statistical notations and programmed categories that would contribute to Herlihy’s analyses of women’s true economic roles in medieval societies. Profession categories included Leather and Furs, and Metallurgy among many others. Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Herlihy then turned his attention to the 15th century catasti (censuses and land registration records that form the basis of property taxation) from Florence, Italy and surrounding areas. Herlihy meticulously transcribed and encoded the volumes of catasti, documenting those 260,000 persons by hand, working on-site at the Archivio di Stato di Firenze, translated them, and then re-transcribed them into early UNIVAC computer punch cards. He devised a code book for repetitive information and used the code to tabulate the information in its entirety. Herlihy’s wife, Dr. Patricia Herlihy, recollects:

“It took years and years, incredible patience and sitzfleisch. I know because I sat next to him for a year in the Archivio di Stato in Florence where he did his Catasto research.”

This extensive research finally culminated in the 1985 book Tuscans and Their Families: A Study of the Florentine Catasto of 1427, co-authored by Christiane Klapisch-Zuber.

Renaissance Italian historian, Anthony Molho describes Herlihy’s contribution to the field:

“Counting was a vital part of Herlihy’s method whether it was the number of people in a tax census or a population’s age and gender distribution, or the consumption of wheat, or the number, gender and provenance of saints per century. And such counting — in simple, or extremely complex, sophisticated ways — imparted upon his work an extraordinary solidity, gave it a dimension that very few works of medieval history — certainly, of Italian medieval history — had until Herlihy showed the rest of us the way.”

“Females in the Richest Quartile of Florentine Households, 1427.” Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Educated at a Jesuit high school and university in San Francisco, David Herlihy married his high school debate opponent, Patricia (who won their debate). Patricia, like David, earned her doctorate, and became an historian and scholar, focusing her own research on Russia. Back to her in a moment…

David Herlihy’s earliest known scholarly work examined the activism of a nineteenth-century San Francisco priest that took a stand against local anti-Catholic bigotry. While still an undergraduate, Herlihy published “Battle against Bigotry: Father Peter C. Yorke and the American Protective Association in San Francisco, 1893–1897” in Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia in 1951. His work then turned toward the papacy and the role of the church in the socioeconomic culture of medieval Italy. Herlihy went on to graduate studies at Catholic University, then Yale University, where he was mentored by medievalist Robert Sabatino Lopez.

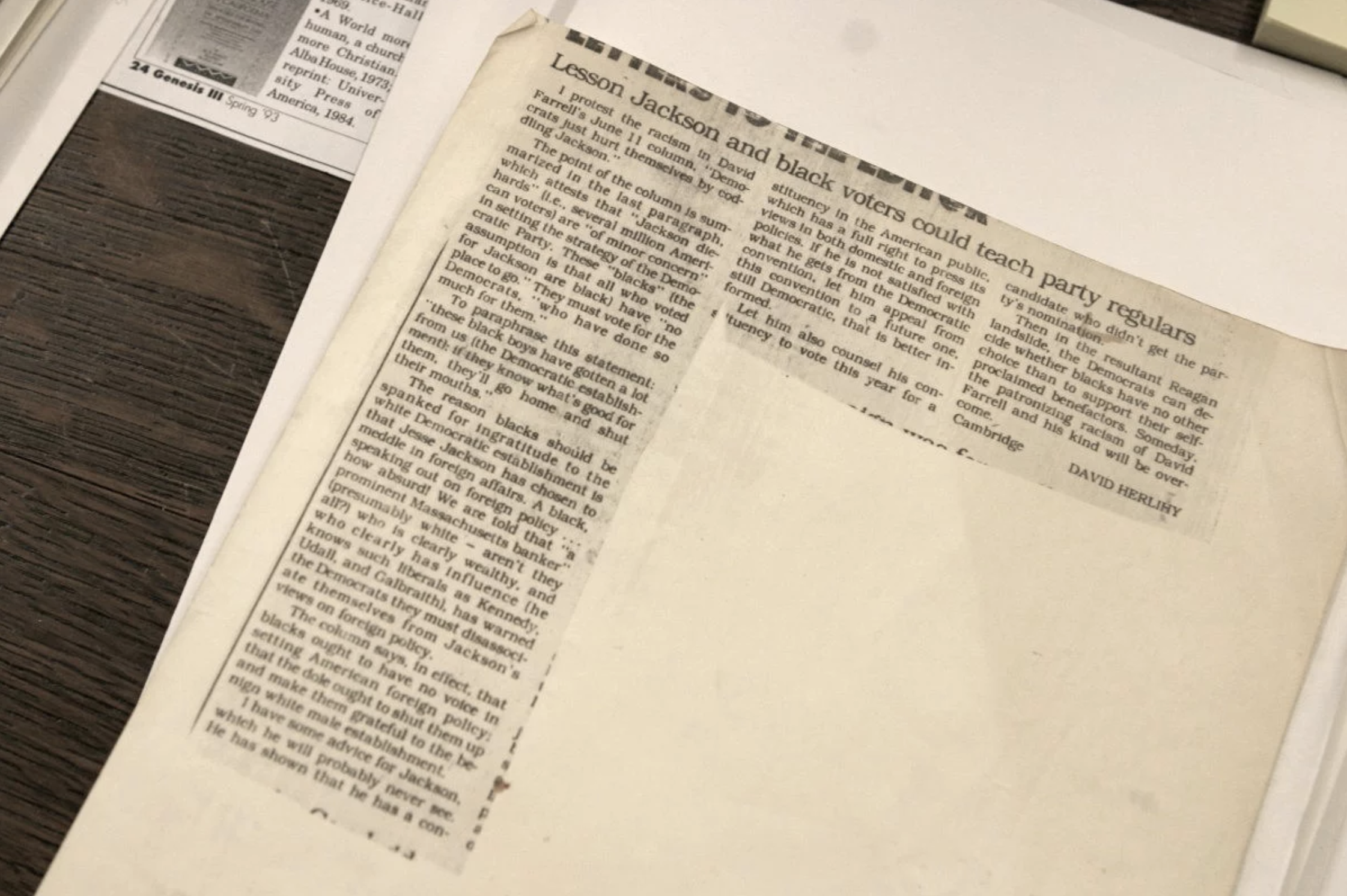

David Herlihy’s Letter to the Editor of the Boston Globe criticizes columnist David Farrell for a racist attitude towards Jesse Jackson. Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Herlihy was the first medievalist to focus research on the roles and lives of women, bringing to light their economic empowerment and robust participation in diverse professions and aspects of commerce — facts that previous medieval historians had failed to report, perhaps due to unconscious, biased assumptions about the roles of women throughout history. Herlihy’s meticulously-collected, and deeply-analyzed data spoke volumes about these previous historical blindspots. Among his other scholarly topics, he conducted research on the papacy and statistical analysis of the gender of saints throughout the centuries, as well as on children and the structure of the family. His book publications included such titles as Land, family and women in continental Europe, 701–1200 (1962), Women in medieval society (1971), and Mapping households in medieval Italy (1972).

Possibly ingrained during his Jesuit education, threads of egalitarianism, social justice and civic responsibility run throughout Herlihy’s papers. This is evident in his collaboration with peers, his mentorship of students, his advocacy for his wife’s professional career, and his voice in social and political fora. Early in his teaching career, Herlihy ran for local political office. He also voiced his protest against what he identified as unjust racial bias in at least one letter to the editor of the Boston Globe:

1980s Harvard University faculty “facebook” showing the Herlihys. Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Herlihy’s egalitarianism extended to his personal life, and included a robust support and advocacy for his wife Patricia’s scholarly pursuits and career as an historian. David Herlihy’s career took off, eventually landing him at the top of his profession at Harvard University with an endowed, lifetime professorship. Throughout their teaching careers, the two would at times share and build on one another’s lecture notes for their respective teaching appointments. Wherever David’s career path landed them, Patricia Herlihy always found adjunct or associate teaching positions at surrounding colleges and universities.

While “Master and Co-Master” (1976–1986) of the undergraduate dormitory Mather House at Harvard College, the Herlihys also acted as advisors to the student organization for Lesbian and Gay Students of Harvard and Radcliffe, as well as for the Catholic Students Association. One writer credits him with helping to found the Women’s Studies program at Harvard University in the early 1970s.

David Herlihy shocked the Harvard establishment when he resigned from Harvard so that he and Patricia could accept “twin” tenured appointments at Brown University. To quote The Harvard Crimson newspaper:

“As a rule, Harvard professors with tenure do not accept appointments from other universities. Generally speaking, no incentives could persuade professors to make a move — neither more money, nor subsidized housing, nor a chaired position can do the trick.”

The Harvard Crimson goes on to quote David Herlihy:

“Patricia’s career was the decisive consideration in our decision to move…She has not had a tenured position at a major American university, nor even a tenure track position. This is what she was trained for, and this is what we both wanted her to have…If you are both academics, it is going to be difficult. Both parties have to be willing to compromise — the interests of both must always be taken into consideration.”

Though his career at Brown University lasted only 5 years from joining the faculty until his death, he continued his social justice activism by commenting on the parallels in social response between the Black Plague of the Medieval period and the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

1987 Essay, “New disease, old fears” written “for the Brown University Community”. Brown University Archives. Photo by Megan Hurst.

Herlihy’s historical scholarship continued to gather many honors and accolades. During this time, Herlihy was nominated and elected to be the president of the American Historical Association, and was honored in Italy with Rotary International’s Galileo Galilei Prize. Near the end of his life, he continued to push the boundaries of his field, researching and proposing ideas about approaching history through a lens of biological sciences — specifically considering the evolution of monogamy. At the time of his death, he was working on three major projects, one of which Dr. Molho describes as a

“staggeringly ambitious project on the Florentine electoral records (Tratte) during the two-and-a-half-centuries of the Republic’s history. At the time of his death, he had nearly completed the task of coding and inputting the tens of thousands of names contained in these volumes, and had written one relatively short essay based on them.”

David Herlihy died on February 21, 1991 of pancreatic cancer. His obituary was published in the New York Times three days later. Publications, honors, and praises continued after his death.

Herlihy’s colleagues in the Department of History at Brown compiled his statistical data to make it available online for use by future scholars (see Online Catasto of 1427 http://www.stg.brown.edu/projects/catasto/). David J. Herlihy’s papers are held at the Brown University Archives. These papers include his original transcriptions of the catasti, research notes, manuscript drafts and revisions as well as professional and personal correspondence.

In the hundreds of articles and books that he published during his career, David Herlihy revealed that computers can help give us a more balanced and accurate view of history.

Links to Dr. Herlihy’s archived research data sets are available at links at the bottom of this page: